Expansion of intrauterine device (IUD) access in Ethiopia

By Meredith Maulsby

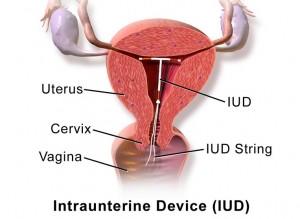

While IUDs have become a source of controversy and subject to new restrictions in the U.S., the government of Ethiopia is actively trying to expand access to IUDs and other forms of long-term birth control to women all over the country. In 2005 the Ministry of Health in Ethiopia began a Health Expansion Program that created paid and trained health extension workers to provide care at the community level. In 2009, the IMPLANON implant program was expanded by training extension workers in how to insert the implant. In 2011, the Ministry added IUD training to this expansion.

While IUDs have become a source of controversy and subject to new restrictions in the U.S., the government of Ethiopia is actively trying to expand access to IUDs and other forms of long-term birth control to women all over the country. In 2005 the Ministry of Health in Ethiopia began a Health Expansion Program that created paid and trained health extension workers to provide care at the community level. In 2009, the IMPLANON implant program was expanded by training extension workers in how to insert the implant. In 2011, the Ministry added IUD training to this expansion.

This summer I am working with FHI 360, specifically focusing on a project that helps the Ministry of Health with monitoring and evaluating the IUD expansion program. FHI 360 helps build the Ministry’s capacity by evaluating training, as well as providing measurement and evaluation training and coaching for health center and Ministry of Health staff. The Ministry of Health has the support of not only FHI 360 for measurement and evaluation, but also Pathfinder and John Snow Inc. for the actual trainings of the health extension workers. Currently, the form of birth control most commonly used in Ethiopia is oral contraceptives, at a rate of 21% of married women and 32% of single women. The Ministry’s project focuses on underserved rural areas whose health centers may not have a trained health worker to administer the IUD or implant. As a 2001 Demographic Health Survey points out, one of the problems regarding family planning in Ethiopia is the inconsistency of birth control access between health centers.

This past week, I visited many rural health centers in southern Ethiopia. They all had varying access to medicine, electricity, water, trained health workers, and larger hospitals. It was an eye-opening experience traveling through Ethiopia visiting the centers and talking with all the different healthcare workers. The health centers were surrounded by beautiful landscape, from jungle-like to flat and dry. Power lines appeared to be abundant, but they either did not quite reach the health centers or were not functional. One health center said they would have to deliver a baby by candlelight if labor went into night because they did not have power in the maternity building, though did in the building across the way. Another center did not have running water, and seemed to carry its water in from a nearby stream. As a result, the number one disease (at that center) was intestinal parasites.

From my observations, most of the health centers have separate rooms for family planning, staffed by a trained health worker who could can insert and extract an IUD or implant. While there were negative aspects to the centers, we were greeted at everywhere we went with friendly and cooperative health workers and administrative staff. Due to unforeseen circumstances, I was unable to travel and observe as much as I would have liked to, however my one trip into the field did allow me to see the positivity that surrounds the health centers despite many daily difficulties.

There is still an unmet need for family planning within underserved areas, and I am thrilled to have been a part of a project and organization that is working to address this need. FHI 360 and the Ethiopian Ministry of Health are not only expanding access but are also ensuring that women are provided safe, comprehensive, and consistent family planning advice and treatment.

Meredith Maulsby is spending her summer interning with FHI 360, a USAID NGO contractor, in Addis Abbaba, Ethiopia. In her first blog post, she discusses an FHI 360 program implemented in conjunction with the Ministry of Health, expanding access to IUDs and family planning services throughout rural Ethiopia.

Source: The Robert S. Strauss Center